Martin Scorcese's letter to the New York Times

Why Make Fellini the Scapegoat for New Cultural Intolerance?

Federico Fellini, renowned for his award-winning career spanning four decades, left an indelible mark on cinema. Upon Fellini's passing in October 1993, a massive memorial service was held at Cinecittà Studios, attended by tens of thousands of mourners. Coinciding with the outpouring of grief, the New York Times published an article by acclaimed photographer Bruce Weber, in which he expressed his frustration with the perceived obscurity and perplexity of artists such as Fellini, John Cage, and Andy Warhol. Weber's dismissive remarks about Cage and Warhol, stating, "I still hear noise and see a soup can," sparked controversy, particularly due to the timing of his piece.

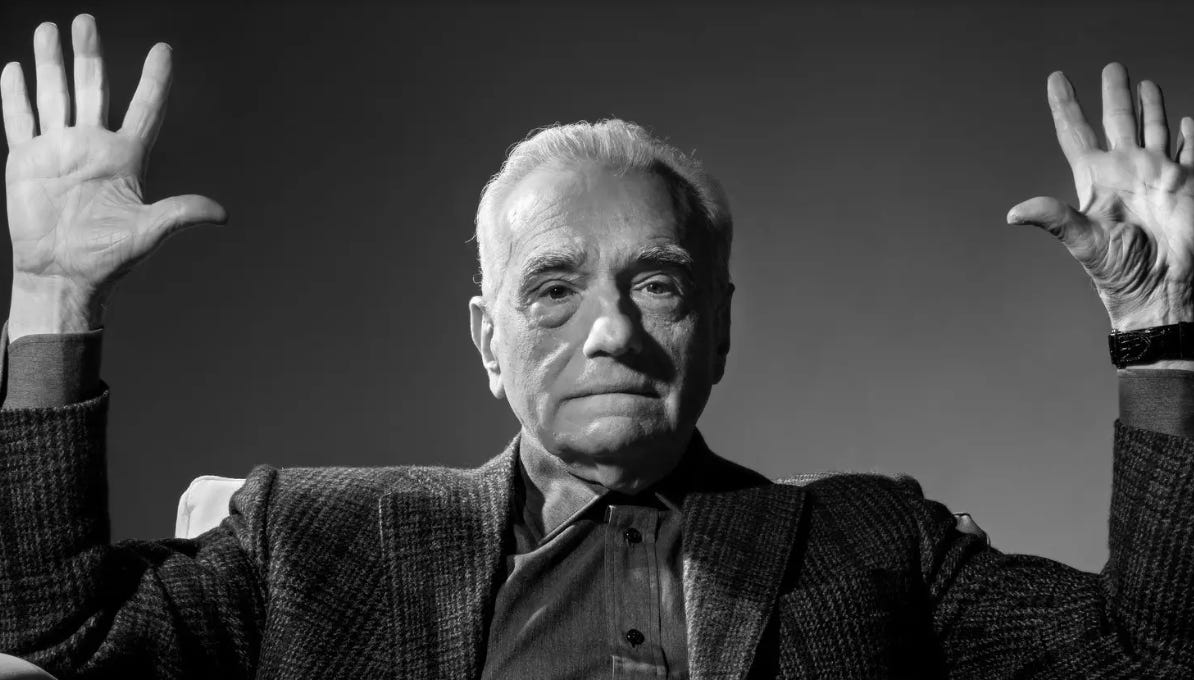

In response to Weber's divisive article, Scorsese penned the letter below to the New York Times, which was subsequently reprinted in the paper. Scorsese's eloquent defence of Fellini and other artists targeted by Weber showcases his humanity, humility and life philosophy at its finest.

Martin Scorsese to the New York Times 19 November 1993

Why Make Fellini the Scapegoat for New Cultural Intolerance?

To the Editor:

“Excuse Me; I Must Have Missed Part of the Movie” (The Week in Review, 7 November) cites Federico Fellini as an example of a filmmaker whose style gets in the way of his storytelling and whose films, as a result, are not easily accessible to audiences. Broadening that argument, it includes other artists: Ingmar Bergman, James Joyce, Thomas Pynchon, Bernardo Bertolucci, John Cage, Alain Resnais and Andy Warhol.

It’s not the opinion I find distressing, but the underlying attitude toward artistic expression that is different, difficult or demanding. Was it necessary to publish this article only a few days after Fellini’s death? I feel it’s a dangerous attitude, limiting, intolerant. If this is the attitude toward Fellini, one of the old masters, and the most accessible at that, imagine what chance new foreign films and filmmakers have in this country.

It reminds me of a beer commercial that ran a while back. The commercial opened with a black and white parody of a foreign film – obviously a combination of Fellini and Bergman. Two young men are watching it, puzzled, in a video store, while a female companion seems more interested. A title comes up: “Why do foreign films have to be so foreign?” The solution is to ignore the foreign film and rent an action-adventure tape, filled with explosions, much to the chagrin of the woman.

It seems the commercial equates “negative” associations between women and foreign films: weakness, complexity, tedium. I like action-adventure films too. I also like movies that tell a story, but is the American way the only way of telling stories?

The issue here is not “film theory,” but cultural diversity and openness. Diversity guarantees our cultural survival. When the world is fragmenting into groups of intolerance, ignorance and hatred, film is a powerful tool to knowledge and understanding. To our shame, your article was cited at length by the European press.

The attitude that I’ve been describing celebrates ignorance. It also unfortunately confirms the worst fears of European filmmakers.

Is this closed-mindedness something we want to pass along to future generations?

If you accept the answer in the commercial, why not take it to its natural progression:

Why don’t they make movies like ours?

Why don’t they tell stories as we do?

Why don’t they dress as we do?

Why don’t they eat as we do?

Why don’t they talk as we do?

Why don’t they think as we do?

Why don’t they worship as we do?

Why don’t they look like us?

Ultimately, who will decide who “we” are?

Martin Scorsese,

NY, Nov19, 1993

Source: New York Times Archives: Link

About Me:

I write to learn. More about me here. Follow @hackrlife on X.